Pictures and Poetry

Pictures and Poetry

In these workshops, we use artworks as the inspiration for writing ekphrastic poetry (poetry inspired by pictures). They are run in partnership with Hereford Mind, Heffernan House, Hereford, to help people maintain their mental health and equilibrium, which is of course all of us! Now in the lockdown we are delivering these sessions via zoom, see poster. If you would like to attend the next session, please message manager@poetry-festival.co.uk. We are very grateful to practitioner Sara Jane Arbury for changing to online delivery and sharing her transcripts for sessions. Scroll down for transcripts of April, May, July, September and October sessions.

Thank you so much Sara Jane for an inspirational workshop today. I got more from it than any other workshop I have done over the past ten years.” – a new participant

Session December 2020

Theme: Quilting.

Click HERE for December Quilting Poetry Workshop transcript, 7 pages

Image: Nan’s Quilt by Sara Jane Arbury

Read Rainbow Poem, created by the participants of this poetry workshop

Session November 2020

EXERCISE ONE: Warm up writing exercise – Me-taphors

Write about yourself in a series of images (metaphors) that describe you and your personality/character as other things (as if you ARE something else).

Be as imaginative and descriptive as you like. Remember it is the little details that bring an image or ‘word picture’ to life, eg:

I am a cork popping from a champagne bottle on New Year’s Eve.

I am a dry pavement taking a daily pounding of feet.

I am a well-thumbed book on a shelf of a second-hand bookshop.

You may ‘open up’ your images further like this:

I am a green leaf on a tree, one of many, and I love to dance and quiver and shake to the wind’s music… I am happy, I don’t want to let go of my tree and float away. I hold on for as long as I can.

You may write about another person if you wish.

Here are some image suggestions to help you:

If you were a landscape or place, what would you be?

If you were a type of weather, what would you be?

If you were a piece of furniture, what would you be?

If you were a vehicle, what would you be?

If you were something that grows in the garden, what would you be?

If you were an item of clothing, what would you be?

If you were a type of food or drink, what would you be?

If you were a time of day, what would you be?

If you were an animal or bird, what would you be?

If you were a piece of music, what would you be?

If you were a colour, what would you be?

Who We Are is the group poem created from this exercise during the workshop

EXERCISE TWO: The theme for this writing exercise is Body Art (body painting and tattoos)

Look at the images, clockwise from L to R on the single sheet of six pictures:

- Nanaia Mahuta, New Zealand’s Foreign Minister

From CNN: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/11/02/asia/new-zealand-foreign-minister-intl-hnk/index.html

New Zealand appointed its first Indigenous female foreign minister to represent what’s shaping up to be one of the most diverse parliaments in the world.

Nanaia Mahuta, who is Maori, the Indigenous people of New Zealand, four years ago also became the country’s first female member of parliament to wear a moko kauae, a traditional tattoo on her chin.

She is related to the late Maori queen and the current Maori monarch. In 2016, Mahuta took part in a traditional moko — or Maori tattooing design — ceremony, and became the first woman to wear a moko kauae to parliament.

Moko are hugely symbolic and contain information about a person’s ancestry, history and status. There are also sacred protocols around t? moko — the act of applying a moko to a person. Historically, moko were applied with chisels but now tattoo machines are often used.

At the time, Mahuta said she hadn’t given a lot of thought to how her tattoo would break new ground. “I’ve just thought about more a longer projection of my walk in life and kind of the way I want to go forward and make a contribution. That’s the main thing for me,” she said.

Rukuwai Tipene-Allen, a political journalist who also wears a moko kauae, said Mahuta’s appointment was hugely significant. “The first face that people see at an international level is someone who speaks, looks and sounds like a Maori,” she said. “The face of New Zealand is Indigenous. It shows that our culture has a place at an international level, that people see the importance of Maori, and the point of difference that being M?ori brings to such a role. Wearing the markings of her ancestors shows people that there are no boundaries to Maori and where they can go.”

More info about moko: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C4%81_moko

Tattoo arts are common in the Eastern Polynesian homeland of the Maori people, and the traditional implements and methods employed were similar to those used in other parts of Polynesia. In pre-European Maori culture, many if not most high-ranking persons received moko. Moko were associated with high social status.

Receiving moko constituted an important milestone between childhood and adulthood, and was accompanied by many rites and rituals. Apart from signalling status and rank, another reason for the practice in traditional times was to make a person more attractive to the opposite sex. Men generally received moko on their faces, buttocks (raperape) and thighs (puhoro). Women usually wore moko on their lips (kauwae) and chins. Other parts of the body known to have moko include women’s foreheads, buttocks, thighs, necks and backs and men’s backs, stomachs, and calves.

Historically the skin was carved by uhi (chisels), rather than punctured as in normal tattooing; this left the skin with grooves rather than a smooth surface. Later needle tattooing was used. Originally tohunga-ta-moko (moko specialists) used a range of uhi (chisels) made from albatross bone which were hafted onto a handle, and struck with a mallet.

Since 1990 there has been a resurgence in the practice of ta moko for both men and women, as a sign of cultural identity and a reflection of the general revival of the language and culture.

In 2016 New Zealand politician Nanaia Mahuta had a moko kauae. When she became foreign minister in 2020, a writer said that her facial tattoo was inappropriate for a diplomat. There was much support for Mahuta, who said “there is an emerging awareness about the revitalisation of Maori culture and that facial moko is a positive aspect of that.”

- Emma Fay – Concept Body Artist

https://emma-fay.co.uk/, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emma_Fay

Emma Fay is an English visual artist specialising in body painting and makeup. Her painted human bodies are documented through photography and film, as well as being created as live installations. Fay has created artwork for commercial domains and her own fine art practice.

UK artist Emma Fay uses concept body artistry to create exhibitions, media and live installations. Painting on the human canvas to create artworks that challenge visual perception, Emma’s approach uses symbolic expression and illusion, while her inspiration is derived from the natural world, humanities and social science.

Born in 1987, Emma’s education in the arts, beauty industry and business allowed her to combine knowledge and skills to manipulate the human form into unique bodies of work that appear in photographed exhibits, live performances and film.

She transforms models into a range of animals, birds and insects and reptiles using water-based paints. She spends about five hours on each creation and many of the models assume Yoga positions that give their bodies the shapes ready for painting.

- Doc Price – the UK’s oldest tattooist

https://www.meettheleader.com/interviews/my-story-doc-price

From online magazine Meet The Leader:

Darrell “Doc” Price is 86. He mightn’t be the world’s oldest tattooist (there is talk of a 101-year-old woman in the Burmese mountains). But he reckons he’s definitely the oldest in Europe. And he’s inked, freehand, something in the vicinity of between 28 and 40 acres of skin.

During that time, he’s witnessed the art form rise from the underground to the mainstream: one in five people now have a tattoo. Even David Dimbleby has a tattoo – a six-legged scorpion on his right shoulder, received when he was a youthful 75.

Doc reckons “social media has a lot to do with it”, along with the influence of friends and partners: “Young people now need to impress other young people.” But he also cites the quality of modern designs. “They’re incredibly beautiful compared to what it was in my day, when you had just seven needle heads and a bit of colouring in a dish.” Back then, you could only choose between red, green, yellow, primary colours. “When I saw my first ever blue ink tattoo, I was jumping up and down with tears.”

He first became fascinated with the art while growing up in Hereford. He’d been mesmerised by a blue butterfly design on the back of a former sailor’s hand, and for the young Doc, the idea that something could live forever on someone’s body was truly magical.

When he was 13, he got one of his own, from an “ancient guy” called Billy Knight in Cardiff. “I had to go and convince my mother, because I come from a family where nobody got tattooed” he says. His tattoo said, simply, ‘Mother.’ His mum loved it, although his father wasn’t best pleased. “Why couldn’t it have said ‘Dad’? So I had to go back the next week. It said ‘Dad.’ I didn’t realise how painful it was going to be, because in those days they didn’t clean their needles properly. It was very, very, primitive.”

He inked his first tattoo, a French Legion cross, around the same time (“You could get away with it because you went to work at 14 in those days”). But he had to work it out on his own. “In my generation, there were no apprenticeships. You were either born into a tattoo family or outside. And if you were born outside you had to teach yourself.”

A few years later, he bought his first brass tattoo machine for £7.10, and set up shop in Barry Island, South Wales, having initially practiced on his workmates at building sites. He’d specialise in motifs such as roses, skulls, swallows and panthers, and his first clients were mainly sailors from the Royal Navy and prostitutes (“pavement princesses”). “We’d use the same, unsterilized needle all week, and the same head chrome. By today’s standard that was totally crazy. And yet… when soldiers served in the British Army in India, they too would be tattooed by tattooists who never cleaned their stuff and tattooed with whatever was used to tattoo before.”

He has studied Japanese tattooing techniques in Japan and eventually settled in Plymouth with his wife, son and daughter, working in his studio at 92 Union Street, as immortalised in a Beryl Cook painting, listening to country music while he works (he’s a big Glen Campbell fan). He doesn’t know exactly how many tattoos he has – “I’ve never counted them” – but among them are ‘autographs’ from long gone well-known tattooists (“This is Les Skues… this is Cash Cooper from Piccadilly Circus…”).

Pain threshold can vary, he says, depending on the individual. “On a scale of one to ten, when it starts off it’s the shock of it, so that’s a six or seven. After a while it goes down to a two or something.” He can use a numbing cream, “but it gets in the hair”. A back tattoo might take between a year or two years – “the tolerance is three to four hours, and then the body starts to break down because it’s seriously uncomfortable.”

He thinks very few people think about the implications of a tattoo’s longevity: “I’ve never worked out the psychology of why somebody would want to get a tattoo. It’s a peculiar and human thing, isn’t it.” And in time, tattoos become “lovely memories… it’s your human history, your personal history of when you had it done.”

The oddest request Doc has ever had was to tattoo a man’s last will and testament on his back. “I didn’t tell him about the spelling mistakes either! I think he just wanted to do it because he had a funny sense of humour.”

And now, after 63 years, Britain’s most venerable skin artist is finally laying down his needle. Any work carried out after this will be for repairs only – and he’s performed plenty of those too, over the past seven decades. Naturally, some of those repair jobs will be the deletion, or rather transforming, of ex-partners’ names. “We’ve always considered ourselves to be in the love business,” says Doc. “We’re either putting the new love on or covering one up.”

- Glenys Coope

https://www.inkedmag.com/tattoos-3/badass-grandma-spends-pension-on-tattoos

From Inked Magazine: 77-year-old Glenys “the Menace” Coope is not your ordinary old-age pensioner. She saves up her pension money so she can afford to get a new tattoo every few months.

Coope’s first set of tattoos started in the 1960s, where she got two hearts on her neck, two swallows on her hands, and a devil and a rose on her back in 1964. However her husband, Walter, had disapproved of her body art, so she removed them in 1985.

Walter has now passed, and the grandmother-of-five, and great-grandmother-of-three, has a tribute tattoo for him on her chest – a love heart with his name on it. But she’s also had sixteen more tattoos since his death. She sports an alien vampire and Medusa, and has her arms, chest and back tattooed.

“I’ve spent £2,000 but it’s been worth every penny,” Coope said. “I’m proud of them and I like them. I’ll get a few more but I won’t have loads. I want a werewolf on my back and then I’ll leave it for a little bit.”

The couple had been married for 54 years. Coope said, “After Walter died I felt that this was something I wanted to do for myself.” Coope visits a local tattoo shop in Derby, England, called Octopus Tattoo Studio. Glenys’ sister, Pearl, was inspired to get her own tattoo after “seeing Glenys’ love affair with inkings.” Pearl, age 84, has a bee tattoo on her leg.

Glenys encourages all older folk to consider getting a tattoo. “I’d tell anyone thinking about getting one to go ahead and get one. It doesn’t matter what other people think,” she said. “I’m living life to its limits. I won’t let my age put me down.”

- John Kenney

https://www.inkedmag.com/tattoos-3/60-year-old-gangster

From Inked Magazine: A life of crime motivated John Kenney to tattoo every inch of his body, including his eyeballs; nose; and tongue, as a fierce act of self-loathing.

Kenney, 60, has tattooed his body as a constant reminder of a violent and turbulent life. That life began with leaving his destructive home at 7-years-old. “I didn’t have a very good family life, there was no love there, just hidings from both parents and even my brothers because they wanted my girlfriend,” he said.

Kenney lived on the streets and suffered abuse. At age 12, he emptied milk bottles on doorsteps to get recycling money for drugs. Then he began breaking into homes before turning pimp. “Yes, you could call me a gangster, I ran drugs, imported them, sold them,” Kennedy said. “They couldn’t control me.” Kenney became a drug mule and tattooed his face to “give him an identity.”

His life was a calamitous cycle of crime and Kenney became suicidal. His fascination with tattoos started when he was 18 years old. It would later bring on Hepatitis C from a dirty needle.

Kenney says his psychologist thinks his tattoos come from self-loathing. Kenney says he “just loves it. Maybe I’ve gone a bit too far, it is starting to look like I am inflicting pain on purpose,” he said. However, that hasn’t stopped him from continuing to ink his skin. “I’ve made friends and got an identity now that I’ve tattooed my face, everyone is curious,” he added.

Kenney says he regrets “half of his life, from the day I was born until I straightened myself.” He now focuses on the life he leads after straightening himself out. He has a permanent home in North Yorkshire, where he speaks to school students about the perils of drugs and dangers of unsafe tattooing. Kenney also advocates for the homeless.

Kenney’s tattoos don’t tell specific stories of specific times in his life, but they are all constant reminders to keep bettering himself.

- Big Head, Big Mouth

https://www.factswt.com/28-weird-tattoos-that-will-make-you-look-twice/

20 years ago, getting a simple tattoo on your arm was not appropriate. Things have changed. Today, the art of tattooing has become more than a simple fashion statement. Youngsters from all over the world inscribe on their bodies inspirational messages or pictures of their loved ones. Japan is one of the rare places where tattooing is still stigmatized because it is associated with the mafia. Most tattoos you will see are representations of hearts, stars, inspirational quotes or animals. Yet, a few “creative” people have decided to stand out and get tattoos that are out of the ordinary.

Tattoos are one of those body art modifications that have gotten accepted by society and are very popular among different people – from skaters and punk rockers to doctors and scientists. The stigma over tattooed people is lifted, and you can now work in a lot of places despite having visible ink on your skin. If you haven’t decided what kind of tattoo you want exactly and where you want it, it is going to be a hard time for you to choose, because the possibilities are endless — artists are getting more and more creative and the techniques used are very advanced. No matter if you just want to hide a scar, mark a memorable moment, or just want a certain realistic image for no particular reason – it can probably be done.

You can find loads of ideas on the Internet that could spark the right idea for your desired tattoo. You must think about it carefully – how big it should be and where it should be placed exactly. You can see for yourself that the right tattoo artist can transform any idea into a work of art.

EXERCISE THREE: Writing Poetry About Body Art Look at the following poems:

Triangle Tattoo by Cheryl Dumesnil

The Wooden Overcoat by Rick Barot

Both poems can be found here:

https://www.tweetspeakpoetry.com/2016/02/18/top-10-tattoo-poems/

The Wooden Overcoat poem can also be found here, with some thoughts about it: http://thepoetrycooker.blogspot.com/2012/04/on-illusion-of-impermance-wooden.html This is an amazing piece because, in my opinion, it explains in perfect and illicit detail why difference in perspectives is one of the most beautiful things we have in our cognitive collective. That we each have our own way of looking at people and objects and moments – that gives these otherwise impermanent things the grace of eternity.’

Choose an image to work with.

- Write a sentence or two about why you chose this picture, how it makes you feel, what it makes you think about / stories / memories

- Next, write a description of details in the picture. Include words that indicate size, shape, colour, light/shade, objects, figures, positions etc.

- Finally, write a poem in response to your picture. If you need inspiration, look back at your answers above.

Remember, there are many different ways to go about this. Here are some further approaches:

- Write about the experience of looking at your chosen image.

- Write a poem about your own or someone else’s tattoo/body art.

- Speculate about how or why the person has these tattoos.

- Write from the point of view of a tattoo – bring it to life and make it think and feel like a human being.

- Write a poem from the point of view of the person with tattoos and/or the tattooist.

- What is being revealed and/or concealed by the tattoos?

- Imagine what was happening while the tattooist was creating this work.

- Write about a tattoo you would like to have.

Your poem could be written in the form or style of one of the example poems (four-line verses / a philosophical poem (The Wooden Overcoat) / one continuous piece / telling a story (Triangle Tattoo).

And, of course, you can write your own poem in your own style!

©Sara-Jane Arbury

Have you uploaded your Poetry of the Woods on our online submission?

The Festival is grateful to Arts Council England the Garfield Weston Foundation, and to Herefordshire Mind where these workshops normally take place

Session October 2020

INTRODUCTION

Ekphrastic Poetry is a form of poetry inspired by works of art. Ekphrastic poems may find new stories about art pieces. It is not simply writing a description about a piece of art. It is more about reinterpreting art works in a new and different way. It can be like having a conversation with the artist or the artistic subject. It is about looking and experiencing artworks in a sensual way and putting your thoughts, feelings, ideas and sensations into words. Information about a piece of art may inform your interpretation or feelings about it.

Look at the photograph of the shark. How do you feel when you view this picture? Now I’ll tell you that it’s a Greenland shark that is 393 years old. It was located in the Arctic and has been wandering the ocean since 1627. Look at the picture again. Have your feelings for the picture changed? How has your response changed?

EXERCISE ONE: Warm-up writing exercise – Alphabet Stories

Alphabet Stories are a fun way to exercise the brain!

Write a 26 word short story where each word follows the pattern of the alphabet.

Follow these steps and rules:

1. Write out the alphabet.

2. Compose a story that follows the alphabet using one word per letter.

3. You may use punctuation and character/place names but they must follow the alphabetical rule.

4. You may use a word that begins with EX when you reach the letter X.

5. The story must make some kind of sense, follow a thread or theme, have a sort of through-line. It is not a list of random words.

6. Give your story a title (this can be anything – it does not follow a special pattern).

Some examples:

A baby calf definitely enjoys fresh grass; however I just keep lambs myself, near open pasture. Quick! Run! See their udders vibrate with X- rated youthful zeal.

Abigail buys chocolate daily. Every Friday George hops into jumpers. Kirsty likes making nutritional oatmeal pies. Quarrelsome Ruby sometimes tells Ursula vile words. Xavier yells, “Zits!”

After breakfast, Christine does exercises for getting healthy, including jogging, karate, leaping. Meanwhile Norman opens paper, quietly reading Sunday Times until vexed wife eXplodes, “You zombie!”

Now try writing another story from Z-A!

EXERCISE TWO: The theme for this writing exercise is Trompe l’oeil (“deceive the eye”)

Useful websites:

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/art-history-101-trompe-loeil

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trompe-l%27%C5%93il

Trompe-l’œil (French for “deceive the eye”) is an art technique that uses realistic imagery to create the optical illusion that the depicted objects exist in three dimensions. It is an art historical tradition in which the artist fools us into thinking we’re looking at the real thing. Whether it’s a painted fly that we’re tempted to brush away, or an illusionistic piece of paper with curling edges that entices us to pick it up, trompe l’oeil makes us question the boundary between the painted world and ours.

Although the term gained currency only in the early 19th century, the illusionistic technique associated with trompe-l’œil dates much further back. It was (and is) often employed in murals. Instances from Greek and Roman times are known, for instance in Pompeii. A typical trompe-l’œil mural might depict a window, door, or hallway, intended to suggest a larger room.

An ancient 5th century Greek story concerns a contest between two renowned painters, Zeuxis and Parrhasius, to determine who was the greater artist. When Zeuxis unveiled his painting of grapes, they appeared so real that birds flew down to peck at them. His rival, Parrhasius, then asked Zeuxis to judge one of his paintings that was concealed behind a pair of tattered curtains in his study. Parrhasius asked Zeuxis to pull back the curtains, but when Zeuxis tried, he could not, as the curtains were included in Parrhasius’s painting—making Parrhasius the winner. Zeuxis said, “I have deceived the birds, but Parrhasius has deceived Zeuxis.”

A similar anecdote says that Zeuxis once drew a boy holding grapes, and when birds, once again, tried to peck them, he was extremely displeased, stating that he must have painted the boy with less skill, since the birds would have feared to approach otherwise.

A fascination with perspective drawing arose during the Renaissance. Many Italian painters began painting illusionistic ceiling paintings, generally in fresco, that employed perspective and techniques to create the impression of greater space for the viewer below. The elements above the viewer are rendered as if viewed from a true vanishing point perspective.

In architecture in particular, trompe l’oeil moved onto an ever-grander scale with decorated ceilings that conjured up the illusion of infinite space – the ultimate test of a master’s skill. In some cases, buildings appear to continue upwards to great heights, while in others the heavens themselves seem to open up.

Other artists added small trompe l’œil features to their paintings, playfully exploring the boundary between image and reality. For example, a fly might appear to be sitting on the painting’s frame, or a curtain might appear to partly conceal the painting, a piece of paper might appear to be attached to a board, or a person might appear to be climbing out of the painting altogether—all in reference to the contest of Zeuxis and Parrhasius.

Trompe l’oeil reached new heights in the 17th century, particularly among Dutch artists, who achieved new levels of realism. One of these, Evert Collier, specialised in trompe l’oeil paintings, or “deceptions” as they were known, and produced many for the English market. His illusionistic letter racks are so convincing, they provocatively tempt us to reach out for the well-thumbed papers tucked behind the leather straps – until we look closer and realise we’ve been fooled.

Trompe l’œil, in the form of “forced perspective”, has long been used in stage-theatre set design, so as to create the illusion of a much deeper space than the existing stage.

Fictional trompe-l’œil appears in many Looney Tunes, such as the Road Runner cartoons, where, for example, Wile E. Coyote paints a tunnel on a rock wall, and the Road Runner then races through the fake tunnel. This is usually followed by the coyote foolishly trying to run through the tunnel after the road runner, only to smash into the hard rock-face.

Today’s most frequent employer’s of trompe l’oeil are perhaps street artists. Bringing the powers of illusionism to a broader audience, they often use trompe l’oeil to startle and stop passers-by in their tracks – whether it’s the illusion of a crater cutting into a city pavement or, in the case of Banksy, painted figures interacting with the fabric of our urban environment.

Look at the attached images – from L to R clockwise on the single sheet of six pictures:

1. Roundstone Street, Trowbridge, Wiltshire by Roger Smith

Located in Roundstone Street in Trowbridge, UK, this trompe l’oeil is thought to be the biggest in the country. The realistic house design, created by artist Roger Smith and Wiltshire Steeplejacks, was installed on the blank wall in October 2003 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of Trowbridge Civic Society.

https://www.gazetteandherald.co.uk/news/7301699.house-mural-attracts-lots-of-second-glances/

2. Escaping Criticism, 1874 by Pere Borrell del Caso

Pere Borrell del Caso (1835 –1910) was a Spanish painter, illustrator and engraver, known for his trompe l’oeil paintings.

There is an interesting article about this painting by writer, Amelia Smithe, from The 8 Percent magazine here:

https://the8percent.com/artwork-of-the-week-escaping-criticism/

3. Camera degli Sposi: Ceiling Oculus, Palazzo Ducale, Mantua, Italy, c.1474 by Andrea Mantegna

Andrea Mantegna (c.1431 – 1506) was an Italian painter and a student of Roman archaeology.

Scroll down to read about this piece of art here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camera_degli_Sposi

Mantegna’s playful ceiling presents an oculus that fictively opens into a blue sky, with cherubs playfully frolicking around a balustrade to seem as if they occupy real space on the roof above. Breaking with the figures from the scenes below, the courtiers who look down from over the balustrade seem directly aware of the viewer’s presence. The precarious position of the plant pot above, as it rests uneasily on a stray beam, suggests that looking up at the figures could leave the viewer humiliated at the expense of the courtiers’ enjoyment. Mantegna’s exploration of how paintings or decorations could respond to the presence of the viewer was a new idea in Renaissance Italy that would be explored by other artists.

4. Trompe-l’oeil with a Partial Portrait of Maria Theresa of Austria, 1762–63 by Jean-Étienne Liotard

Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702 – 1789) was a Swiss painter, art connoisseur and dealer.

One outstanding feature of Liotard’s paintings is the prevalence of smiling subjects. Generally, portrait subjects of the time adopted a more serious tone.

Liotard enjoyed great renown as a portraitist. But in later life, he made a group of trompe l’oeil paintings with a more mischievous edge, showcasing his virtuoso skill at evoking different textures and creating convincing visual illusions. Made for his own delight rather than as commissions, these baffling works demonstrate Liotard’s technical mastery and his eccentric tendencies.

17th-century Dutch art was much admired by Liotard, and may have inspired his own trompe l’oeil paintings; he produced around ten. In this work, Liotard deepens the visual puzzle by incorporating real wood. Half the panel is left unpainted, apart from a small painted sculptural medallion that makes it look like a cover revealing the portrait beneath. It’s a clever and sophisticated conceit that calls to mind the famous curtain painted by Parrhasius centuries earlier.

More info about this painting can be found here:

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/art-history-101-trompe-loeil

5. Le Radeau de Lampedusa by Pierre Delavie

Pierre Delavie created this hard-hitting piece (translated as “The Raft of Lampedusa”), in collaboration with the French Reception and Support Office for Migrants in 2017. This trompe l’oeil depicts a boat of refugees capsizing in the River Seine and aims to alert Parisians to the urgency of the situation of refugees drowning in the Mediterranean Sea. The original image was taken by the Italian Navy in 2016. Delavie explained that he was extremely touched by the events in the Mediterranean and that when he saw the image it upset him. He cut it out and kept it, then eventually recreated it on the wall of the River Seine.

6. Tunnelvision by Blue Sky

Blue Sky née Warren Edward Johnson, Postwar / Trompe-l’oeil American, b. 1938

This dramatic piece is 50 ft x 75 ft and shows a craggy portal leading to a fantasy moon. Created by local artist Blue Sky, who has more work in the area, it can be found in a parking lot in downtown Columbia. The artist does regular touch ups to make sure it stays as realistic as possible but despite tales to the contrary it has not been crashed into by any confused local drivers.

Images 5 and 6 can be found here, alongside other examples of trompe l’oeil art:

https://www.creativebloq.com/art/trompe-loeil-12121498

EXERCISE THREE: Trompe l’oeil Poetry

Look at the following poems:

1. Trompe l’Oeil – Mary Jo Salter

https://poetryarchive.org/poem/trompe-loeil/

Info about the poem here:

http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-trompe-loeil/#gsc.tab=0

Mary Jo Salter’s poem “Trompe l’Oeil,” which provided the title for her 2003 collection ‘Open Shutters’, describes an artistic style found in Genoa, Italy, and throughout Europe: that of painting realistic murals on the outside walls of houses and buildings, so real that people passing by are fooled, at least briefly, into mistaking the painted images for the things they represent. Salter uses this particular style of painting to spark a meditation on the nature of reality and the arts in general, finding insincerity in both the fake shutters that stand beside a real window and the French word “oeil” itself, which can be considered deceptive or a lie because it presents a final “l” to the eye but not to the ear (it is not pronounced the way it is spelled if one assumes each letter stands for a specific sound).

Stylistically, the poem shows the deft control of rhyme, off-rhyme, and rhythm that readers have come to expect of her words. Salter’s technical elegance is balanced with a light sense of humour that makes the most of ordinary ironies, such as the contrast between laundry piled up inside the house and imitation clothes hung to dry on a painted clothesline on the wall outside. The poem manages, in just a few lines, to treat readers to a new way of looking at the world and of looking at how artists depict the reality that others simply experience.

2. Trompe L’oeil – David Chorlton

Read the poem and his short commentary here:

https://thirdwednesdaymagazine.org/2020/07/19/trompe-loeil-david-chorlton/

David Chorlton, a frequent contributor to Third Wednesday magazine, said, “These are strange times, and sending messages-as-poems out from home seems a way of breaking out of social distancing. These poems have spent some time in isolation themselves, but they stood out on my revisiting unpublished work as having a silence or atmospheric note that echoes where we are in March of 2020.”

Choose an image to work with.

• Write a sentence or two about why you chose this picture, how it makes you feel, what it makes you think about / stories / memories

• Next, write a description of details in the picture. Include words that indicate size, shape, colour, light/shade, objects, figures, positions etc.

• Finally, write a poem in response to your picture. If you need inspiration, look back at your answers above. Remember, there are many different ways to go about this. Here are some further approaches:

• Relate the work of art to something else it makes you think of.

• Write about the experience of looking at the art.

• What is being revealed and what concealed?

• Speculate about how or why the artist created this work.

• Imagine what was happening while the artist was creating this work.

• Speak to the artist of the painting, in your own voice.

• Write in the voice of the artist.

Your poem could be written in the style of one of the example poems (three-line verses / using rhymes and half-rhymes / one long continuous piece).

And, of course, you can write your own thing in your own style!

©Sara-Jane Arbury

Have you uploaded your Poetry of the Woods on our online submission?

The Festival is grateful to Arts Council England the Garfield Weston Foundation, and to Herefordshire Mind where these workshops normally take place

Session September 2020

EXERCISE ONE: This is a warm-up writing exercise called Univocal Writing

This is a form of writing that only uses one vowel. Look at these examples of univocalics (poems that only use one of the five vowels: in these cases the letter ‘o’). Low Owl by John Rice: and an extract from Ron’s Knockoff Shop by Luke Wright See Luke perform the whole poem here:

Write a poem, story or piece that only uses one of the five vowels, in this case the letter ‘e’. Use this sheet of ‘e’ words to help you!

Now have a go at writing other pieces using only one vowel each time. This exercise makes you put words together that you wouldn’t do ordinarily. A playful exercise where you can experiment with words.

Credit and thanks to Leanne Moden at Nottingham Writers’ Studio for the resource. I attended an excellent online poetry workshop with Leanne and this was one of the writing exercises she set.

EXERCISE TWO: The theme of this exercise is SELF-PORTRAITS

I thought of exploring this theme because of the recent rise in use of video platforms. We can now see ourselves in situations like online meetings, social gatherings etc. We are part of a Gallery in Zoom. We can see ourselves as self-portraits. This is new for us. We are not used to seeing ourselves interact and communicate with people. How do we feel about that? Do we modify our behaviour/expressions? What about reading body language? How different is it to ‘live’ and ‘real’ communication and interaction? Have we noticed things about ourselves that are interesting, surprising, unwanted? Have there been any revelations?

Here is some further information about the theme:

A self-portrait is a representation of an artist that is drawn, painted, photographed, or sculpted by that artist. Although self-portraits have been made since the earliest times, it is not until the Early Renaissance in the mid-15th century that artists can be frequently identified depicting themselves as either the main subject, or as important characters in their work. With better and cheaper mirrors, and the advent of the panel portrait, many painters, sculptors and printmakers tried some form of self-portraiture. The genre is venerable, but not until the Renaissance, with increased wealth and interest in the individual as a subject, did it become truly popular.

Look at the following paintings and consider how they work as art, why they were painted, how they were created, how they make you feel, etc.

From L to R clockwise:

1. Self-Portrait, 1889 by Vincent Van Gogh

Vincent Willem van Gogh (30th March 1853 – 29th July 1890) was a Dutch post-impressionist painter who is among the most famous and influential figures in the history of Western art. In just over a decade, he created about 2,100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings, most of which date from the last two years of his life. They include landscapes, still lifes, portraits and self-portraits, and are characterised by bold colours and dramatic, impulsive and expressive brushwork that contributed to the foundations of modern art. He was not commercially successful, and his suicide at 37 came after years of mental illness, depression and poverty.

Van Gogh suffered from psychotic episodes and delusions throughout his life and, though he worried about his mental stability, he often neglected his physical health, did not eat properly and drank heavily. His friendship with Gauguin ended after a confrontation with a razor when, in a rage, he severed part of his own left ear.

Van Gogh was unsuccessful during his lifetime, and he was considered a madman and a failure. Today, Van Gogh’s works are among the world’s most expensive paintings to have ever sold, and his legacy is honoured by a museum in his name, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which holds the world’s largest collection of his paintings and drawings.

This painting, with the artist looking sideways, was painted while the artist was in an asylum in Saint-Rémy, France. Van Gogh admitted himself to the small asylum in May 1889 and was struck down by a severe psychotic episode in July that lasted for a month and a half. In a letter to his brother, Theo, dated 20 September 1889, Van Gogh referred to this self-portrait as “an attempt from when I was ill”.

It has been noted that the self-portrait depicts someone who is mentally ill; his timid, sideways glance is easily recognisable and is often found in patients suffering from depression and psychosis. The image is dominated by a greenish-brown tone. Louis van Tilborgh, professor of art history at the University of Amsterdam, said Van Gogh was frightened to admit he was in a similar state to other residents at the asylum. “He probably painted this portrait to reconcile himself with what he saw in the mirror: a person he did not wish to be, yet was,” he said.

“This is part of what makes the painting so remarkable and even therapeutic. It is the only work that Van Gogh is known for certain to have created while suffering from psychosis. It belongs to a group of pictures that show something of his mental health problem and how he dealt with it, or tried to deal with it.”

Van Gogh would have been looking in a mirror as he was painting so the ear in view is his right one, not the one he severed with a razor blade. The ear in this painting is vague and presumably deliberately so. Within a year he was dead, aged only 37, after he shot himself in an apparent suicide.

2. Self-Portrait As The Allegory Of Painting, 1638-9 by Artemisia Gentileschi

Artemisia Gentileschi (8th July 1593 – c.1656) was an Italian Baroque painter, now considered one of the most accomplished seventeenth-century artists. In an era when women had few opportunities to pursue artistic training or work as professional artists, Artemisia was the first woman to become a member of the Accademia di Arte del Disegno in Florence and had an international clientele.

Artemisia was known for being able to depict the female figure with great naturalism and for her skill in handling colour to express dimension and drama.

She was invited to London in 1638 by Charles I and produced Self-Portrait As The Allegory Of Painting there when she was 46 years old. She holds a brush in one hand and a palette in the other, cleverly identifying herself as the female personification of Painting, described as such in the king’s inventory. The work is also, however, a self-portrait: as a woman artist, Artemisia identifies herself as the female personification of Painting.

Artemisia wears a brown apron over her green dress and seems to be leaning on a stone slab used for grinding pigments in which the reflection of her left arm is visible. The area of brown behind her has been interpreted as background, or as a blank canvas on which she is about to paint. Particularly striking is the rolled up sleeve of her right arm, where fluid strokes of white delineating the edge of her sleeve meet the brown shadow of exposed ground.

As a self-portrait the painting is particularly sophisticated and accomplished. The position in which Artemisia has portrayed herself would have been extremely difficult for the artist to capture, yet the work is economically painted. In order to view her own image she may have arranged two mirrors on either side of herself, facing each other. Depicting herself in the act of painting in this challenging pose, the angle and position of her head would have been the hardest to accurately render, requiring skilful visualisation.

Few of Artemisia’s self-portraits survive and references to them in the artist’s correspondence only hint at what others might have looked like. It is clear that Artemisia’s image was very much in demand among 17th century collectors, who were attracted by her outstanding artistic abilities and her unusual status as a female artist.

3. Interior With Hand Mirror (Self-Portrait), 1967 by Lucian Freud

Lucian Michael Freud (8th December 1922 – 20th July 2011) was a British painter and draughtsman, specialising in figurative art, and is known as one of the foremost 20th-century portraitists. He was born in Berlin, the son of Jewish architect Ernst L. Freud and the grandson of Sigmund Freud. His family moved to England in 1933 to escape the rise of Nazism. He served at sea with the British Merchant Navy during the Second World War.

His early career as a painter was influenced by surrealism, but by the early 1950s his often stark and alienated paintings tended towards realism. Freud was an intensely private and guarded man and his paintings are mostly of friends and family. They are generally sombre and thickly impastoed, often set in unsettling interiors and urban landscapes. The works are noted for their psychological penetration and often discomforting examination of the relationship between artist and model.

In his self-portraits, Freud turns his unflinching eye firmly on himself. Spanning nearly seven decades, his self-portraits give a fascinating insight into both his psyche and his development as a painter – from his earliest portrait, painted in 1939, to his final one executed 64 years later. When seen together, his portraits represent an engrossing study into the process of ageing.

Here is an interesting article about Interior With Hand Mirror (Self-Portrait) by art critic Martin Gayford (scroll down to read it).

“This little picture from the 1960s presents two crucial tools for Freud: a window and a mirror. The first was important because – after his youth – all of his work was done indoors, in a studio. There were various reasons for this. One was that he found the “changing light outside was a difficulty”. Another was that, always intent on privacy and averse to what he called “attention”, he hated being watched by strangers as he worked, as would occur outdoors. The result was that for him “the quality of light in the studio is of great importance”.

Freud was a connoisseur of light. As we talked one day in his Kensington studio, he exclaimed, “The light is very good here just at the moment, better than it was a few minutes ago!” I asked if he meant it was brighter. “Clearer,” he replied. Doubtless he felt the same about the window in his studio at Gloucester Terrace, a street near Paddington. He must have spent countless hours next to it. This picture is, obviously, a portrait of that window, but also a self-portrait. Since artists cannot, of course, see themselves directly, all self-portraits have to be mediated. Since Freud did not use photography, that meant his self-portraits were all pictures of reflections in mirrors – such an important fact for him that he took to adding the word “reflection” to the title of self-portraits.

As he told Lawrence Gowing, “the information gathered from a mirror is a very different kind of information”. The reason was, he felt, because the light was different. So Interior With Hand Mirror (Self-Portrait) is a depiction of these two kinds of light: one coming in from the street, the other reflected behind the subject. It is also a meditation, at once factual and poetic, on the difficulty of seeing oneself.”

4. Self-Portrait, 1902 by Gwen John

Gwendolen Mary John (22nd June 1876 – 18th September 1939) was a Welsh artist who worked in France for most of her career. Her paintings, mainly portraits of anonymous female sitters, are rendered in a range of closely related tones. Although she was overshadowed during her lifetime by her brother Augustus John and her lover Auguste Rodin, her reputation has grown steadily since her death.

In 1916, John wrote in a letter: “I think a picture ought to be done in 1 sitting or at most 2. For that one must paint a lot of canvases probably and waste them.” Her surviving oeuvre is comparatively small; oil paintings which rarely exceed 24 inches in height or width. The majority are portraits, but she also painted still lifes, interiors and a few landscapes. She wrote, “…a cat or a man, it’s the same thing … it’s an affair of volumes … the object is of no importance.”

It became John’s habit to paint the same subject repeatedly. Her portraits are usually of anonymous female sitters seated in a three-quarter length format, with their hands in their laps. One of her models wrote of John: “She takes down my hair and does it like her own … she has me sit as she does, and I feel the absorption of her personality as I sit”.

Her notebooks and letters contain numerous personal formulae for observing nature, painting a portrait, designating colours by a system of numbers, and the like. Their meaning is often obscure, but they reveal John’s predilection for order and systematic preparation.

Gwen John’s art, in its quietude and its subtle colour relationships, stands in contrast to her brother’s far more vivid and assertive work. Critical opinion now tends to view Gwen as the more talented of the two. Augustus himself had predicted this reversal, saying “In 50 years’ time I will be known as the brother of Gwen John.”

Here is an interesting article about Gwen John’s self-portrait by artist Celia Paul in Frieze Masters:

“In this self-portrait, her hair is parted in the middle. She looks like Emily Dickinson, who also parted her hair in the middle. Both Gwen John and Dickinson are famous for their reclusiveness. John’s gaze is direct but withdrawn. She holds the secret of her inner life intact. The painting glows from within like a dark room lit only by firelight. A brown shawl is half-slipping off her shoulders: a brilliant device that adds movement to a composition which may otherwise be too stiff. The whole image is held together by an interplay between restraint and freedom. A locket is held in place at John’s throat by a narrow, black ribbon. The face on the locket is in profile and stone-coloured. I feel that it is the face of her mother, who died when John was only eight years old. The loss of her mother must have been a sadness that she always held close to her. The quietness and intensity of this image affects me deeply. I have learned from John that you don’t need to shout in order to make an impact.”

5. Soft Self-Portrait With Fried Bacon, 1941 by Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, 1st Marquess of Dalí de Púbol (11th May 1904 – 23rd January 1989) was a Spanish Surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship and the striking and bizarre images in his work. Born in Figueres, Catalonia, Dalí received his formal education in fine arts at Madrid. Influenced by Impressionism and the Renaissance masters from a young age, he became increasingly attracted to Cubism and avant-garde movements. He moved closer to Surrealism in the late 1920s and joined the Surrealist group in 1929, soon becoming one of its leading exponents.

Dalí’s artistic repertoire included painting, graphic arts, film, sculpture, design and photography, at times in collaboration with other artists. He also wrote fiction, poetry, autobiography, essays and criticism. Major themes in his work include dreams, the subconscious, sexuality, religion, science and his closest personal relationships.

After World War II, Dalí became one of the most recognized artists in the world and his long cape, walking stick, haughty expression, and upturned waxed moustache became icons of his brand. His boastfulness and public declarations of his genius became essential elements of the public Dalí persona: “every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dalí”.

Amy Plewis on the website Art-Theoria says:

“I have found the weird and macabre works of Dalí both compelling and comforting. When it came to studying self-portraits I returned to Dalí for inspiration because I felt that to depict myself accurately I could not paint my reflection in a mirror, but what I saw in it; sensation over reality.

Megalomaniac and provocateur are words associated with Dali, which when paired with his extreme appearance (his trademark moustache and flamboyant fashion sense) creates a caricature, untouchable on a human level. This is how he interacted with the world around him, but a self-portrait is an opportunity to say a lot more with honesty and without a facade, in this case quite literally.

The painting can be looked at on a basic level, without getting too deep into ideas and theories. As a Surrealist Dalí blurred the line between reality and imaginary in an often dark and haunting manner. Creating art could unlock the subconscious mind, allowing us to experience and explore our true selves in an unrestricted way. He wrote “to the outside world I assumed more and more the appearance of a fortress, within myself I could continue to grow old in the soft, and in the super-soft.”

At its most simplistic this is a painting of an outer appearance, a mask or flayed face. Dalí presents it to us as an object to be revered and studied, it is an artefact on a plinth. It could also be seen as a trophy, a memento of a victorious quest that immortalises the artist. Upon its stone base the title has been inscribed in an authoritative font. It is a trompe l’oeil of a self-portrait, but it isn’t about the artist’s technical ability, it is about transcribing something deeper through paint on canvas.

In the absence of eyes (often described as the windows to the soul), a recognisable facial expression, a posed body with clothes and adornments set against a backdrop, we may feel that we have little to read in terms of traditional visual information. Or perhaps we can feel undistracted so that we may reach another dimension of understanding. There are a few symbols though; ants, bacon, and crutches – objects that reoccur in his work. The ants that are crawling into the tear duct represent death and decay. Bacon can represent food and sustenance, while on the other a slice of a dead animal flesh that will rot. Its crisp and undulating texture contrasts with the softness of the mask, making it look all the more flaccid and fragile. The crutches suggest weakness or vulnerability, without them the face would become a featureless liquid pile.

The overriding thing this painting says to me is that this famous moustachioed face was just a veneer, something that Dalí hung up when out of the public eye. Something mortal that would die with him. He described it as “the glove of myself” and denied any psychological content – in fact he called it anti-psychological. But it is interesting that as a painter who continually painted his thoughts, fears, fantasies, and dreams openly, that when it came to a self-portrait we are denied a psychological reading of a man with a brain that was so interesting.

While the physical ‘self’ is exposed, the inner ‘self’ will always be somewhat private, and a self-portrait cannot tell us what a person is really about at their core. Most of the time we do not fully know ourselves, and even if we did how that could be translated into a painting. Faces are rarely transparent, and no-one knows what’s going on behind the surface of the most composed and controlled self-portraits in art history. Yet we can relate to this elusiveness, and I find that a consolation.”

6. Self-Portrait With Thorn Necklace And Hummingbird, 1940 by Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo (6th July 1907 – 13th July 1954) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artefacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country’s popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to explore questions of identity, post-colonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society. Her paintings often had strong autobiographical elements and mixed realism with fantasy.

Following a terrible accident in her youth and with only herself for a model, Kahlo’s self-portraits usually depict great pain, physical as well as mental. Her 55-odd self-portraits include many of herself from the waist up, and also some nightmarish representations that symbolize her physical sufferings.

Kahlo’s paintings often feature root imagery, with roots growing out of her body to tie her to the ground. This reflects in a positive sense the theme of personal growth; in a negative sense of being trapped in a particular place, time and situation; and in an ambiguous sense of how memories of the past influence the present for either good and/or ill. In Kahlo’s paintings, trees serve as symbols of hope, of strength and of a continuity that transcends generations. Additionally, hair features as a symbol of growth and of the feminine in Kahlo’s paintings. In most of her self-portraits, she depicts her face as mask-like, but surrounded by visual cues which allow the viewer to decipher deeper meanings for it. Aztec mythology features heavily in Kahlo’s paintings in symbols like monkeys, skeletons, skulls, blood, and hearts.

EXERCISE THREE: Write a poem inspired by the theme of SELF-PORTRAITS

This part is about writing your poem. Look at these example poems on the theme:

Self-Portrait In The Nude – Allison Funk (American poet)

Rembrandt’s Late Self-Portraits – Elizabeth Jennings (scroll down to read the poem) An analysis of Jennings’ poem is here.

Self-Portrait – Adam Zagajewski (poet, novelist, essayist, born in Lwów in 1945 and is a prominent member of Poland’s contemporary poetry scene).

Think about the form, patterns and repetitions in the poems, the ‘word music’, what each poem is saying to the reader, how you feel when you read them, how they reflect the theme, imagery, metaphors, etc.

Choose an image from the paintings we have looked at to work with. What does it make you think about? What do you notice about it? Memories? Stories?

Here’s a way of getting started:

• Write notes about why you chose this work of art, how it makes you feel, and/or what it makes you think about.

• Next, write a detailed description of the work of art. Be specific enough so that someone else could clearly imagine the work of art in his or her mind after reading your description. Be sure to include words that indicate size, shape, colour, light/shade, objects, figures, positions etc.

• Finally, write a poem in response to your work of art. If you need inspiration, look back at your answers above. Also, remember there are many different ways to go about this.

Here are some approaches your poem could take:

• Relate the work of art to something else it makes you think of.

• Write about the experience of looking at the art.

• What is being revealed and what concealed? Disguise?

• Speculate about how or why the artist created this work.

• What are the clothes saying? What does the pose say? Props?

• Imagine what was happening while the artist was creating this work.

• Speak to the artist of the painting, in your own voice.

• Write in the voice of the artist.

• Do we know someone from a self-portrait / not know them / which is it?

Your poem could be written in the style of one of the example poems – a self-portrait in words about yourself, almost as a monologue, like Adam Zagajewski’s poem; a structured poem in verses with a rhyme scheme like Elizabeth Jennings’ poem; an imagination of how you would paint your physical self and its changes over time in a stylistic form like Allison Funk’s poem.

And, of course, you are perfectly free to write about the theme in your own way and in your own style!

Session July 2020

EXERCISE ONE: This is a warm-up writing exercise called Lines About Headlines

Choose a headline from this list and write a poem/piece inspired by it. This may be stream-of-consciousness thoughts, a newspaper item, a diary entry, a piece from the point of view of a character involved in the story, an interview…etc.

The headlines have been collected from newspapers since March 2020. They can be used as prompts to write lockdown poems from different angles.

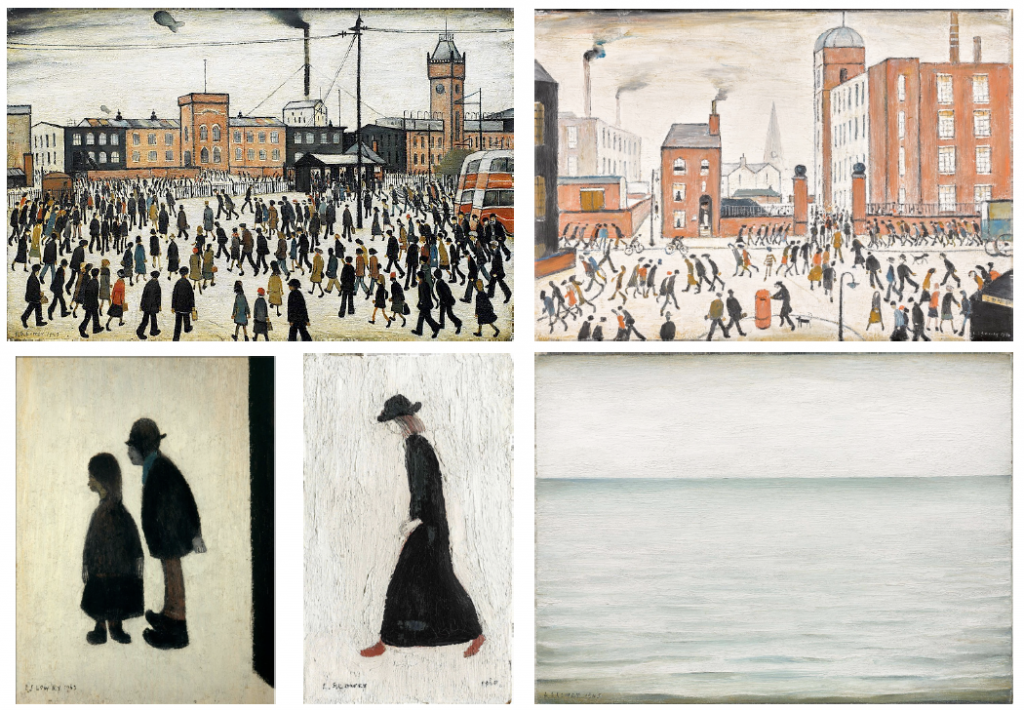

EXERCISE TWO: The theme of this exercise is THE ART OF L S LOWRY

This part is about looking closely at Lowry’s artworks and considering example poems.

Let’s begin with some quotes by Lowry on art:

“You don’t need brains to be a painter, just feelings.”

“I am not an artist. I am a man who paints.”

“If people call me a Sunday painter, I’m a Sunday painter who paints every day the week.”

“My ambition was to put the industrial scene on the map, because nobody had done it, nobody had done it seriously.”

“I wanted to paint myself into what absorbed me … Natural figures would have broken the spell of it, so I made my figures half unreal. Some critics have said that I turned my figures into puppets, as if my aim were to hint at the hard economic necessities that drove them. To say the truth, I was not thinking very much about the people. I did not care for them in the way a social reformer does. They are part of a private beauty that haunted me. I loved them and the houses in the same way: as part of a vision.”

“I am a simple man, and I use simple materials: ivory black, vermilion, Prussian blue, yellow ochre, flake white and no medium. That’s all I’ve ever used in my paintings. I like oils … I like a medium you can work into over a period of time.” While Lowry often claimed to only use these five colours, he also used titanium white and zinc white. This use of other paints became helpful when determining that works were genuine and not forgeries.

Lowry on painting his Seascapes:

“It’s the battle of life – the turbulence of the sea … I have been fond of the sea all my life, how wonderful it is, yet how terrible it is. But I often think … what if it suddenly changed its mind and didn’t turn the tide? And came straight on? If it didn’t stay and came on and on and on and on … That would be the end of it all.”

There is a lot of information about the life and work of L S Lowry here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L._S._Lowry

For more information about Lowry, visit: https://thelowry.com/

Information about Lowry’s work can also be found here: https://www.christies.com/features/10-things-to-know-about-LS-Lowry-8657-1.aspx

Take a close look at the following artworks by Lowry. Consider how they work as art, how and why were they created, how the artworks make you feel, etc…

Pictures from L to R clockwise: L.S. Lowry: Going To Work (1943) LS Lowry’s iconic painting ‘Going to Work,’ was commissioned in 1943 at the height of the Second World War by the War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC). Heavy industry was playing a crucial role in the war effort and the WAAC wanted to reflect that in their art collection. Filled with all the signature features that have made Lowry such a much-loved artist, ‘Going to Work,’ is set in front of the Mather & Platt engineering works in Manchester as the crowd of matchstick workers flow into the factory. The white sky and ground, originally thought to be snow, is in fact an evocation of industrial haze. At the time, Lowry was paid 25 guineas for the commission and finished ‘Going to Work’ in three months. Once complete, it went on display at home and abroad as the WAAC attempted to promote Britain’s Second World War effort; The Rush Hour (1964); Seascape (1945); Girl With Red Shoes (1960); Two People (1962)

Now look at these poems:

Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs by Brian Burke & Michael Coleman:

For a film of the song, visit here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kmopSVOMSsU

For the lyrics, visit here: https://lyricsplayground.com/alpha/songs/m/matchstalkmenandmatchstalkcatsanddogs.html

Notice the rhyme scheme used in the lyrics of this song (aa b cc b in the verses) and the use of a chorus.

L S Lowry by Howard Chapman:

https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/l-s-lowry/

(Notes from the author: Common to most urban landscape paintings of L. S. Lowry is a curious pale yellow hue, reminiscent of the snow scenes by Dutch masters but peopled by the peasantry of Salford. The background was borne of a practical technique, layering white paint on the bare canvas or wood and then scraped smooth. This provided a clear base for the composites of industrial buildings and strange isolated folk who so fascinated Lowry. Growing up in Old Trafford in the 50’s I remember that yellowed light, later banished by ‘smokeless zones’ and the ‘Clean Air Act’. Lowry evokes that light for me: dank November nights carrying ‘Pink’ paraffin home, the can cutting into cold hands, the menacing smog filling me with dark imaginings of bogey men and murders. I remember, too, when I first started work in Trafford Park, once the largest industrial estate in Europe. The AEI Metrovic factory I travelled to features in a number of Lowry’s paintings. The early morning bus filled up with workmen coughing up phlegm. The gloom seemed to be outside and inside and within, like a thorough shroud for body and soul)

Notice the descriptions, the sounds of the words and the ‘word music’ in this poem.

Haikus by John Kitching:

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ZV7JlTpXeAQC&pg=PA209&lpg=PA209&dq=the+pen+in+my+hand+kitching&source=bl&ots=4NFmfIkgn3&sig=ACfU3U0yS_WTzosn2ZjBPapNoakg1QfYdg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiXy5zojqzqAhVlRRUIHbBpD0kQ6AEwAXoECAsQAQ#v=onepage&q=the%20pen%20in%20my%20hand%20kitching&f=false

An example of a poem called a renga – linked haikus on a common theme. Haikus fit well with Lowry’s artwork as they are also seemingly simple forms that say so much more than the sum of their parts. A haiku is a short poem of three lines with a syllable structure of 5 syllables in the first line, 7 syllables in the second and 5 syllables in the third line. You can link haikus about a common theme together like beads on a string to create a longer poem called a renga.

Think about the form, patterns and repetitions in the poems, the ‘word music’, what each poem is saying to the reader, how you feel when you read them, etc.

EXERCISE THREE: Write a poem inspired by the theme of The Art Of L S Lowry

This part is about writing your poem.

Choose an image to work with. Make notes about it. What does it make you think about? What do you notice about it? How does it make you feel? What do you think about when you look at it?

Next, write a detailed description of the work of art. Include words that indicate size, shape, colour, light/shade, objects, figures, positions etc. You may notice details in the painting that you hadn’t before.

Finally, write a poem in response to your work of art. If you need inspiration, look back at the notes you have made. Remember, there are many different ways to go about this.

Some suggested approaches:

• Write about the scene or subject being depicted in the artwork.

• Relate the work of art to something else it makes you think of or a memory.

• Write about the experience of looking at the art.

• Speculate about how or why the artist created this work.

• Imagine a story behind what you see presented in the work of art.

• Imagine what was happening while the artist was creating this work.

• Speak to or directly address the artist or the subject(s) of the painting, in your own voice.

• Write in the voice of the artist.

• Write in the voice of a person or object depicted in the artwork.

Your poem could be written in the form and/or style of one of the example poems – eg: using the particular rhyme scheme of the Matchstalk song; including lots of details and description of a lived experience as in Howard Chapman’s poem; adopting a form such as a renga…

And, of course, you are perfectly free to do your own thing!

Enjoy!

©Sara-Jane Arbury

Have you uploaded your Poetry of the Woods on our online submission?

The Festival is grateful to Arts Council England the Garfield Weston Foundation, and to Herefordshire Mind where these workshops normally take place

Participants’ poems inspired by this session

Session May 2020.

EXERCISE ONE: This is a warm-up writing exercise called Words In Names

Write your full name on a piece of paper (or use someone else’s name).

Now spend 5 minutes listing as many words as you can find that appear in your name. Try to find at least ten words and try to find words with lots of letters, for example, I have the word JANUARY in my name SARA-JANE ARBURY!

Next write a short piece/poem/story using as many of the words in your list as possible. You may repeat any found words.

This is also an unusual way to create unique messages for friends and family members by using their names as the starting point!

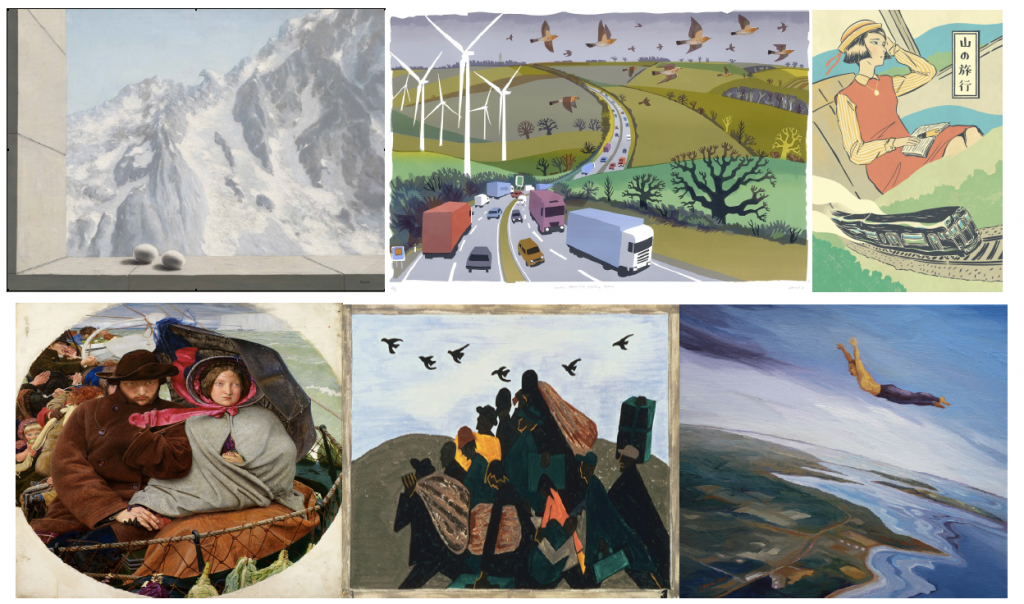

EXERCISE TWO: The theme of this exercise is JOURNEYS

This part is about looking closely at artworks and considering two example poems on this theme.

“People have always moved around the world. Early humans were nomadic, travelling in search of food, shelter, and safety. Today, people move for many different reasons, including economic, political, cultural, religious, and environmental. Sometimes, events beyond people’s control, like war or natural disaster, leave them displaced and forced to migrate. Other times, people migrate voluntarily, perhaps in search of better work opportunities or a different lifestyle. For many artists, their own migrations and those of their ancestors shape their identities and the art they produce. As people move, they bring their traditions, knowledge, and beliefs with them. Often, as much as they absorb the culture of their new home, they influence it with their own traditions.”

(Preface to Migration & Movement exhibition, MoMA, Manhatten)

Take a close look at the following artworks. Consider how they work as art, how and why were they created, how the artworks make you feel etc…

Paintings top row left to right:

René Magritte: Le Domaine d’Arnheim

https://www.christies.com/features/When-artists-dream-of-far-flung-lands-10390-3.aspx (follow the link and scroll down to the picture)

The Belgian Surrealist, René Magritte, named this painting after the short story The Domain of Arnheim by Edgar Allan Poe. In German, the word ‘Arnheim’ means ‘home of the eagle’, which is reflected in Magritte’s imperious bird-mountain (look closely!)

Magritte had never been to the Alps, but in 1926 he came across a photograph of the mountain range in a travel brochure and used it as inspiration for his bird-mountain. He was so pleased with the results that he painted the Alpine vista another nine times. It became one of his most enduring symbols.

Carry Akroyd: Winter Thrushes Head Home

https://www.carryakroyd.co.uk/prints/ (follow this link and click on the title of the picture to call it up)

Third painting no commentary

Paintings bottom row left to right:

Ford Madox Brown: The Last of England

https://medium.com/thinksheet/how-to-read-paintings-the-last-of-england-by-ford-madox-brown-73eb9e41840f

This painting is in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Brown began it in 1852 when emigration from England was at a peak, with over 350,000 people leaving that year. The painting depicts a man and his wife seeing England for the last time. The white cliffs of Dover are disappearing behind them in the top right of the picture.

In the foreground a row of cabbages hang from the ship’s rail, provisions for the long voyage. In the background are other passengers, including a pair of drunken men and a family. The father is barely visible except for the pipe he holds; his daughter has her arm around a curly-haired boy. There is a fair-haired child eating an apple behind the man’s shoulder.

In order to mirror the harsh conditions in the painting Brown worked mostly outside in his garden, and was happy when the weather was poor – he recorded his feelings of delight when the cold turned his hand blue, as this was how he wanted it to appear in the painting. He was seen as strange by his neighbours who saw him out in all kinds of weather. His diary noted that the “ribbons of the bonnet took me 4 weeks to paint”.

Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series, Panel No. 3 (1940-41)

https://www.phillipscollection.org/collection/browse-the-collection?id=1153&page=3

Follow this link to find out more about the life and work of Jacob Lawrence

https://lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org/

The Migration Series is a group of sixty paintings by African-American painter Jacob Lawrence which depicts the migration of 1.6 million African Americans to the northern United States from the South that began in the 1910s. Lawrence conceived of the series as a single work rather than individual paintings and worked on all of the paintings at the same time, in order to give them a unified feel and to keep the colours uniform between panels. Viewed in its entirety, the series creates a narrative that tells the story of the Great Migration. Lawrence created the sixty paintings in the series in 1940–41 when he was twenty-three years old.

The panels depict the dire state of black life in the South, with poor wages, economic hardship and a justice system rigged against them. The North offered better wages and slightly more rights, although was not without its problems.

Now look at these two poems about journeys: Sea Fever by John Masefield

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/54932/sea-fever-56d235e0d871e

and Out Of Africa by Grace Nichols

https://prezi.com/pudzhk1_zo3-/out-of-africa-by-grace-nichols/ (scroll down for the poem)

Think about the form, patterns and repetitions in the poems, the ‘word music’, what each poem is saying to the reader, how you feel when you read them, etc.

Jerri Finch: Abundant Splendor

http://jerrifinch.com/painting-journeys.htm (follow the link and click on the image of the man in the air on the far right of the screen as you look at it)

EXERCISE THREE: Write a poem inspired by an artwork on the theme of Journeys.

This part is about writing your poem.

Choose an image to work with. Make notes about it. What does it make you think about? What do you notice about it? How does it make you feel? What do you think about when you look at it?

Next, write a detailed description of the work of art. Include words that indicate size, shape, colour, light/shade, objects, figures, positions etc. You may notice details in the painting that you hadn’t before.

Finally, write a poem in response to your work of art. If you need inspiration, look back at the notes you have made. Remember, there are many different ways to go about this.

Some suggested approaches:

• Write about the scene or subject being depicted in the artwork.

• Relate the work of art to something else it makes you think of or a memory.

• Write about the experience of looking at the art.

• Speculate about how or why the artist created this work.

• Imagine a story behind what you see presented in the work of art.

• Imagine what was happening while the artist was creating this work.

• Speak to or directly address the artist or the subject(s) of the painting, using your own voice.

• Write in the voice of the artist.

• Write in the voice of a person or object depicted in the artwork.

Your poem could be written in the style of one of the example poems.

And, of course, you are perfectly free to do your own thing!

©Sara-Jane Arbury

Have you uploaded your Poetry of the Woods on our online submission?

The Festival is grateful to Arts Council England the Garfield Weston Foundation

Participants’ poems inspired by this session

Session April 2020.

EXERCISE ONE: A warm-up writing exercise called In Our Mind’s Eye.

It takes the concept of Slow Looking as its inspiration. Here is an article about Slow Looking from The Guardian:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/shortcuts/2018/jul/24/why-taking-it-slow-in-an-art-gallery-could-change-your-life

Choose a picture that you have displayed on a wall at home. Slow Look at it like this: Study the picture for 5 minutes. Really look at it. Absorb yourself in the picture. Then write a piece about it for 5 minutes without looking at it. What do you remember about it? What impressions do you take from it? Is there something there you haven’t noticed before? What is its essence? Finish your piece by telling us why you have the picture displayed on your wall.

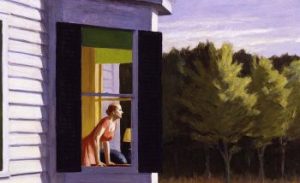

EXERCISE TWO: The theme for this writing exercise is THE ART OF EDWARD HOPPER

Before you begin, take a look at this picture of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Claude_Monet_-_Nymph%C3%A9as_(1905).jpg

This link will take you to an article called Backing into Ekphrasis: Reading and Writing Poetry about Visual Art by Honor Moorman. The article contains two poems inspired by Monet’s painting. One poem speaks to the artist in a spectator’s voice and the other adopts the voice of the water lilies themselves.

http://www.tnellen.com/cybereng/ekphrasis.pdf

Now look at these paintings by Edward Hopper (1882-1967, American painter and printmaker):

Room In New York

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Room_in_New_York#/media/File:Room-in-new-york-edward-hopper-1932.jpg

Cape Cod Morning https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/cape-cod-morning-10760

Cape Cod Evening https://www.edwardhopper.net/cape-cod-evening.jsp

Room In Brooklyn (scroll down for picture)

http://www.thelonelypalette.com/episodes/2016/12/28/episode-13-edward-hoppers-room-in-brooklyn-1932

Night Windows https://www.edwardhopper.net/night-windows.jsp

Hotel By A Railroad https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hotel-by-a-Railroad-Edward-Hopper-1952.jpg

Choose one of these images to work with and make notes about it. Why did you choose this picture? How does it make you feel? What does it it make you think about? Memories?

Make notes describing the picture – colour, light/shade, objects, figures, positions, shapes, etc.

Finally, write a poem in response to your picture. Look back at your notes for inspiration. Here are some suggested approaches:

Write a poem in the style of one of the example ‘Monet’ poems (addressing the artist directly as a spectator or in the voice of someone or something depicted in the picture).

Imagine a story behind what you see presented in the picture. What else is going on in the scene?

Write about the experience of looking at the picture. Relate the picture to something else it makes you think of, for example, a memory or your current situation.

With thanks to Backing into Ekphrasis: Reading and Writing Poetry about Visual Art by Honor Moorman

You might enjoy this article about why Edward Hopper is a telling artist for the coronavirus age

© Sara-Jane Arbury

Have you uploaded your Poetry of the Woods on our online submission?

The Festival is grateful to Arts Council England the Garfield Weston Foundation